Articles | Roll of Honour | Photographs

Blaxhall’s History between 1700 and 1900

1700 - 1800

Information relating to the 1700’s is in some respects even sparser than that regarding the preceding century, with no population counts available and limited other meaningful information, although on a positive note the surviving records are in increasingly recognisable form rather than the Latin and olde English of earlier documents. One thing we do know to get us started is that the manorial ownership was attributed to Mr John Bence in 1705 and to Dudley North in 1729. (North, the son of notable London merchant and party host Sir Dudley North, had purchased nearby Glemham Hall and it’s estate some years earlier in 1709). Staying with the subject of the rich and powerful, a peek at the 1705 general election stats reveals that the majority of Blaxhall’s voters (there were less than 10 of them!) were placing their loyalties with the Tories.

One, rather sad, early occurrence we should perhaps note in this section is the death of Elenor Mills. We know very little about Eleanor’s life save for one small, but rather unmissable detail; her headstone, with its neatly inscribed date of October 6th 1721, is the oldest surviving grave marker to be found in St. Peter’s churchyard.

Three other events worthy of mention in this period are the appearance of the Ship Inn, built c1700, the murder trial of Margery Beddingfield, and the arrival in the village of one David Ling. The Ship (originally believed to have been The Sheep) has played a prominent role in the village from it’s earliest days until recent times; in the 18th & 19th centuries it was the meeting and preparation place for the Blaxhall Company of Sheepshearers as well as the haunt of local shepherds, but perhaps gained even more fame (or infamy!) at the time for its constantly rumoured connection with smuggling - rumours indeed which also involved much of the rest of the village and left several amusing anecdotes for posterity, such as the story that menfolk would suddenly commence loud singing while sitting indoors at night, a habit allegedly driven by the desire to hide the noise of passing illicit wagons from their womenfolk, while the shepherd would conveniently be along early next morning with several hundred hooves to erase any wheel tracks. On a practical level smuggling & poaching provided additional income, alcohol, nourishment, and even entertainment, until relatively recent times, with the cellar of The Ship still retaining the iron hooks once used for hanging poached game. (Smuggling was big business in 18th century Suffolk, with enormous amounts of tea, tobacco, brandy and gin arriving at isolated places such as Sizewell before being distributed inland. Even the Clergy could be bribed into secreting dodgy goods in the church!) In a rather more official capacity The Ship served as the main meeting place for legitimate village business for many years prior to the building of the school and village hall, with gatherings as diverse as Coroners inquests, weddings, and the meeting of The Burial Club all taking place in the old "Big Room". One incident involving both sheep and an inquest took place in November 1744 when Blaxhall butcher John Wyard took it upon himself to procure a sheep from its rightful owner in Farnham during the middle of the night; evidently Mr Wyard must have had something of a reputation for illicit moonlit operations since he was confronted the next morning by the parish constable bearing a search warrant and detailed description of the missing creature. The said sheep, now decidedly dead and partially dismembered, was found hanging inside the back of the shop, with the predictable aftermath being butcher Wyard’s arrest and trial. His sentence is unknown, but given the seriousness of livestock theft at the time it seems very possible that a date was drawn up with the hangman’s rope. Knowing the severity of punishments and assumed God-fearing nature of the populace at the time one might be forgiven for thinking that crime was pretty rare, but offences crop up with surprising frequency: Another example shortly after the ovine caper is the burglary committed by one Augustine Davy, an imposing Norfolk born labourer who was jailed in the 1760s for breaking into the house of John Pope and appropriating 3 pairs of worsted stockings (worsted stockings, as opposed to ordinary woollen stockings, were generally seen as a preserve of the wealthy - being more refined, breathable and lighter). Mr Davy, upon his arrest, was found to have a curious array of oddments about his person that included several pieces of silver, a large chisel, an unusual fluted bureau key and a pound of black tea.

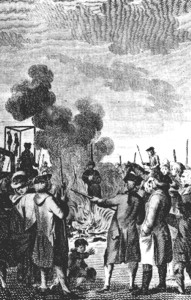

Margery (aka Ann) Beddingfield was christened in St Peter’s Church on the 6th of June 1742, the daughter of farmer John Rowe. Her particular claim to fame is not a desperately pleasant one, but undeniably makes her nationally relevant; she was the last woman in England to be burnt for petty treason. Margery married Sternfield farmer John Beddingfield on July the 3rd 1759, and in the early years enjoyed a very happy marriage, but in 1761 a young farmhand called Richard Ringe moved into the household and began a steamy affair with Margery. Within 6 months the lovers were plotting the demise of farmer Richard, and on the night of July 27th 1762 Richard entered his unsuspecting victim’s bedroom to carry out the ghastly deed. After a brief struggle John Beddingfield was dead, and an astonishing verdict of "death by falling out of bed" appeared to put the culprits in the clear, but fate caught up with them a little while later when a former servant spilled the beans. Following a brief, clear cut trial Richard Ringe was hung for murder at Rushmere St Andrew on the 8th of April 1763, while Margery, for her part in the plotting, was burnt at the stake (Left) - the accepted, and expected, punishment for petty treason (husband murder).

Born in Swilland in 1754 David Ling moved with his family to Campsea Ashe c1758 before leaving his parents and moving to Blaxhall, possibly in search of work, c1773. Whilst he played no important role in village history per se, what he did do was father (by 2 wives) some seventeen children between 1776 & 1809, the beginning of a veritable dynasty that saw 100’s of Lings born in Blaxhall over the next 150 years (as well as spreading profusely to the surrounding towns and villages). So extreme was the situation by the end of the 19th century that Blaxhall was earning mention in literature and correspondence because of the "exceedingly large number of people that had the name of Ling"; a situation that led to the use of numerous nicknames, such as Croppy Ling, Straight Ling, Flancher Ling or Nacker Ling, in order to make distinction between individuals who shared the same Christian name.

The arrival of new people was very big news 300 years ago, since the village was responsible for its own finances the fresh arrivals would invariably mean either extra income or outlay. The "poor" of the time had to be supported by a fund known as the Poor Relief, the coffers of which were filled by rates collected from the village’s landowners (both large and small) then distributed by the Overseer. A natural consequence of this system was that newcomers who looked likely to require poor payments were not warmly welcomed, with most being subject to the system of Examination which required a person to prove their ability to support his/her self for 12 months before being granted Settlement in their new village. Passed some 100 years earlier in 1662 the Settlement Act was intended to stop poor people from moving from one area to another continually claiming handouts. As a result, those who fell on hard times while in a foreign village could often expect short shrift, commonly being removed to their village of settlement or, in particularly harsh cases, simply dumped in a ditch outside the village boundary. If you were fortunate enough to be settled and qualify for the Poor Relief (commonly - widows, orphans, the very old or disabled) you could expect really quite reasonable support; some of the items listed in Blaxhall’s poor payments include children’s clothes (including breeches, hats & gloves), doctor’s visits, house maintenance & furnishings, and even wedding costs. The total annual Poor Relief paid out in 1776 was £95. 2s. 2d.

Hodskinson’s 1783 map of Suffolk shows Blaxhall in reasonable detail and reveals that while the rectory had already appeared, complete with it’s stable block, the rest of "Rectory Road", shows no evidence of houses at all - what is now Stone Common was then just an empty field. There are also surprisingly few houses around Mill Common; indeed most of the 30 of so buildings are scattered widely in groups of no more than 2 or 3. Many of those scattered houses, including the major farms, can be matched up with those still present today - but others appear in locations where today no obvious trace of dwellings remains. The road layout is remarkably unchanged, with just a couple of minor roads appearing/disappearing, although other maps from just 20-30 years earlier or later do show considerable differences; the highway referred to today as Station Road (and clearly visible in 1783) for example was little more than a footpath in 1760, with the wonderful name of Peddler’s Path, while a quite major trackway spurring off Peddler’s Path and passing across the back of the church, past the original great west door in the tower, carried the even more delightful title of Holy Gate Path. The aforementioned great west door and window were stopped up with brick, possibly in order to provide better support for the tower following the 1683 repairs, although the window may have been sacrificed earlier with the fitting of the bells in 1655, since much of the bell rope support woodwork protrudes into the old window space. Then again - this may have occurred in 1863 when the current bell ringers platform came into being. (Perhaps an expert on church architecture will visit us one day and unravel all these little mysteries!).

1800 - 1850

By 1801 the population had grown to 373, with the number of houses totalling 38 - making, one would imagine, for some very cramped bedrooms and breakfast tables! Perhaps this necessarily high level of intimate living had something to do with the founding of "The Friendly Society" with its 45 members in 1803. That year also showed a much-increased Poor Relief of £373. 14s. 3d. The big rise in population over the previous 100 years may have been helped by, or even partially encouraged by, an increase in available work due to a gradual change to more labour intensive arable farming, with barley, wheat and turnips becoming increasingly popular at the expense of traditional Blackface sheep. The scene was still very different from that of recent agriculture however, Red Polled cattle roamed where today we see Friesians, and Devon Bullocks still pulled most of the ploughs that would later be associated with Suffolk Punches. Although those Suffolk Punches could do far more work and had been around in some form since around 1500 - with every example alive today being descended from a single foal born in Ufford in 1768 - the bullocks clung on in some places until the late 1800s, thanks to their much lower food consumption and the fact they could be eaten after retirement.

A map the north-west end of the village from around 1800 reveals a long since lost cottage along from Beversham bridge, perhaps one of the several victims of the housefires that were frighteningly common at the time. Also present are the bridge, watermill and nearby windmill (see below); Gorse Farm was marked as "Town House" and among the more imaginative field names were "Further Rotten Meadow" and "Stonehorse Meadow". A slightly later map of the commons from 1809 shows that the first houses have appeared on Stone Common (then called Church Common) while the other end of the village now has a couple of houses present on Ship Corner. Next to these houses can be seen two sites of encroachment, with land sectioned off but houses yet to appear; the two characters responsible were brothers George & William Ling, sons of reproductive champion David. Whilst one may have expected housing requirements to be rather basic at the time one local resident clearly had other ideas - we’re told that one of the cottages next to The Ship was adorned by an enormous coat of arms, carved from oak, originating in Sudbourne Hall, and purchased at auction for £30 (around £1400 in today’s money!). Sadly, no trace now remains.

A couple of accidental deaths around this time serve to remind us just how dangerous day to day existence could be before the invention of such mundane things as electric lighting and health & safety laws. The first unfortunate victim was 6 year old Daniel Sawyer, who, in 1809 was playing outside the mill (where his father William worked) with several other children when he was struck on the head by one of the sails, resulting in a fractured skull. The local doctor was called but in the absence of hospitals, ambulances and today’s medical expertise there was little he could do. Daniel survived the night but, predictably, died the following day. The second case worth a mention is that of Susan Row, she was doing nothing more adventurous than reading a newspaper in her own home one evening in 1811 when she made the mistake of falling asleep in her chair and slumping a little too close to the candle burning on the adjacent table; the flame caught hold of her clothes and within a matter of minutes the widow Row was no more.

1817 witnessed the first (though not last) transgression by members of the aforementioned Ling clan, when George (the encroacher) and Samuel (another son of founding father David), became a little too closely acquainted with a pheasant: "On 20 November 1817, George Ling, aged 28 years and his brother Samuel Ling, 24 years, were committed to Woodbridge Gaol on the charge of poaching game. They were charged that on the night of 19th November between the hours of four and six in the morning they illegally entered a piece of enclosed ground in the parish of Blaxhall with the intent of taking and killing game. Samuel Ling was armed with a gun and George Ling with a bludgeon with which he violently assaulted and beat gamekeeper Benjamin Fosdick. At the General Quarter Sessions held in Woodbridge on 14 January 1818, they were found guilty and sentenced to twelve months in the county gaol."

In 1827 several Roman (more recent research suggests Iron Age) urns were unearthed from the tumulus on the common, perhaps as a result of increasing activity by the fast growing population, which numbered 525 by 1831. The number of houses had increased in line with the population - up to 57 - but that still meant an average of nine people in each and every small cottage. Of those 525 people almost ½ were children or teenagers, while the male female split was a remarkable 262/263. The vast majority of menfolk at this time were still agricultural labourers or traditional craftsmen, jobs they would have begun at 12 or 13 and continued throughout their life until they were literally too old to physically continue, at which point they would become reliant on any meagre savings, kind relatives, or the Poor Relief to see out their twilight years. The Poor Relief in question was also on the rise, hitting £602. 8s. in 1832, but the whole system was about to change (for the worse) in 1834 with the introduction of the New Poor Law; this revised arrangement (intended to cut costs) saw financing and control taken away from individual parishes and an increase in the use of workhouses - unpleasant institutions where many people were forced to see out their years in demeaning, almost prison like, surroundings. Given the rapidly growing population and potentially grim outlook for those out of work, it’s not really surprising that several men - both single and with families - began leaving the village; with further pressures such as the decline in the wool trade and surplus of labour following the end of the Napoleonic wars many travelled surprisingly long distances in search of a fresh start, despite the rudimentary transport of the time; by the 1830s & 40s Blaxhall born folk were to be found as far afield as Durham, Worcestershire, London and Lancashire, working as everything from coal miners and sailors to iron smelters and gardeners. The pressure for jobs at home was aptly demonstrated in neighbouring Tunstall, when in 1844, James Friend was transported to Australia for sending a threatening letter to farmer William Cockrel: part of the letter read; "...Farmer, we are starving: we will not stand this no longer, this gang is 680; rather than starve, we are determined to set you on fire; you are robbing the poor of Thier living by employing thrash mans machines. These promises will soon take place, if you dont soon alter,..."

Back in Blaxhall education was at least gaining in importance, with 2 daily schools operating in Blaxhall in 1833; the same year that village elder James Smith was unlucky enough to be struck and killed by lightning.

20 years on from the pheasant incident, David Ling’s offspring were again to find themselves on the wrong side of the law; on 29 March 1837 William Ling (the other encroacher), aged 47 years, along with his half brother John, was committed to Woodbridge Gaol and charged with stealing a pig from a barn yard in Farnham belonging to farmer Crisp Plant. At the General Quarter Sessions held at Woodbridge on Wednesday 5th April 1837 both William and John were convicted over the theft of said pig. William was convicted of stealing the pig and John of receiving and eating it. They had no intention of going easily, John initially refusing to allow Constable Daniels (see next paragraph) to search his house, while brother William locked the pantry and withheld the key. Ultimately however the searches went ahead and a variety of incriminating porcine portions were unearthed around house and garden. Both men received the same sentence - transportation to Tasmania for 14 years. The men left England on board the vessel Susan on 5 August 1837, which arrived in Tasmania on 21 November and where John remained until his death in 1865. William however, did not survive the passage. He died on 17th October and was buried at sea. John’s unfortunate wife Charlotte and 4 children found themselves forced into the workhouse at Wickham Market, where the two boys died the following year. Charlotte was last seen living alone as a laundress in London in 1851, the same year her husband’s sentence was due to end some 8000 miles away. William’s wife managed to cling to their Blaxhall home until her death in 1842, but several of her children also arrived in the workhouse a few years later. The Ling boys weren’t the only Blaxhall residents suffering from the harsh laws of the time though, 3 years later in 1840 20 year old labourer Walter Youngman found himself sentenced to lifelong transportation for burglary.

By the early 1840s the ever expanding nature of the village is shown by the presence of no less than 4 shoemakers, as well as 2 blacksmiths, 8 farmers, a joiner, a cooper, a tailor, 2 shops, and a postman. One of those shops is on Stone Common, where William Whitehand was providing the grocer & draper roll that was to continue from the same premises for the next 140 years, while, two doors down, Robert Daniels was a busy man, serving as Parish Clerk, Constable and shoemaker in the house still know as "Shimmackers" to this day. Robert’s parents, like William Leggett the blacksmith, had come to the village to ply their wares around the turn of the century, and probably built the house themselves. Robert’s son John, the last Daniels to cobble in Blaxhall, was to become one of the village’s many suicide victims 20 years later. A quick glance at the the map reveals that most of what we consider to be the village’s "old" houses have by now appeared, although many of them were yet to begin sprouting the numerous extensions and wings we see today. 1844 brought with it a rather grim discovery, when numerous skeletons were unearthed during excavations close to the parish boundary, just beyond Pump Square. They were believed to come from the graveyard of St Mary’s Church, Dunningworth; no trace now remains of the said edifice, but we know it was still in use in 1561 and appeared to be shown as a complete church on John Speede’s map of 1610. By 1730 however it was long since disused and much decayed, with only scant ruins visible. These ruins were observed by Hodskinson 50 years later, (when he wrongly labelled them as those of Snape Abbey), were also noted by the National Gazatteer in 1868, and were allegedly still visible in 1926. Two more tragic mishaps at this time reminds us that the village workplace was still very dangerous, especially for children: this time the first casualty was Gerard Ling (Great Grandson of old friend David), the unfortunate 11 year old was riding on one of the horses used to turn the huge 5ft French burr mill stones at Lime Tree Farm when he jammed his head against part of the machinery, dying almost instantly as a result. The second was Joseph Row, whose father and brothers can be seen harvesting on page one of the photo section; twelve year old Joseph was taking a seed drill along the road to Langham bridge when the horse was spooked and took off down the road, dragging the drill over young Joseph and killing him with a blow to the head.

Eleven years having now passed since the Ling boys’ pig incident Blaxhall was to be the scene of a rather more dramatic crime. On 9th December 1848 a gang of 8 poachers, all from nearby villages, were confronted by the gamekeeper and his companions in the Alder Carr wood. The ensuing passionate clash witnessed the exchange of much harsh and indignant language before several of the poachers fired their guns at the game keeping contingent, seriously injuring brothers Isaac and William Clarke (who described the experience as being "struck in the breast like hail when the wind blows"). Fortunately the injured men both made good recoveries, while the offenders were all later captured and sentenced to be transported for up to 15 years. The arrival of outside outlaws wasn’t going to put our own rogues out of their stride however, as our local Ling boys sought to keep up their reputation for mischief; this time the star of the show was Walter, son of George the poacher. Young Walter’s troubles began in 1843 at the age of 16, when he was sentenced to 14 days hard labour for trespass in pursuit of game; the next 14 years saw a further 6 sentences being handed out to Walter, for everything from illegal fishing and stealing grass, to bastardy and pilfering a partridge. (He also found time to marry and have 8 kids). Also in action during the 40s was young David, son of the other original poacher Samuel; David’s troubles began at just 11 years old when he was caught taking pheasants eggs (14 days hard labour) and continued into the 1850s when he again fell foul of a tempting fowl in 1852 (2 months hard labour).

1850 - 1900

By 1851 the population was approaching its peak, with a total of 577 people living in some 121 houses - an apparent huge increase from just 38 houses only 50 years earlier - although it’s probable that the 1851 figure is actually referring to households, which would give a house number of perhaps 70-80. Coinciding with this population peak was the building of the new national school in the same year. Also new was the Ipswich to Lowestoft railway line; the route through Blaxhall was being planned as early as 1845, but eventually opened in 1859, with crossing guard’s cottages being erected at Beversham, Blaxhall Hall, and on the Campsea Ashe boundry at Blackstock Wood - where the now defunct branch line to Framlingham used to spur off. The link to Snape Maltings joined the main line near Burnt House Farm; incorporating 3 wooden bridges on its way across the marshes it could only be serviced by special small engines. Despite the presence of a passenger booking hall at Snape the line was only ever used for goods, which during the war included rubble brought from bomb damaged London and intended for local gun emplacements, while contrary to popular belief the railways were not always better in the old days - not only did trains to Snape regularly fail to show up, but in 1860 the staff of Framlingham station were sent to trial for robbery with violence! Modern conveniences were showing up in other locations too, the church had its own hot air stove, which was treated to a new cylinder and tune up in 1857; part of a veritable spending spree that saw numerous new fixtures and repairs, including the replacing of 2 bell wheels, a tower window, and a new vestry door, among much else. The same outlay of cash also saw the bricking up of the doorway to the rood loft. Not everyone was turning up to enjoy these changes though, a Wesleyan Methodist following had taken hold, most probably meeting in one of the larger houses.

Getting back to the land, a review of agriculture in 1854 shows more than 50% arable farming, with less than 20% permanent pasture. No shortage of sheep though, a density of some 70 per acre made us one of the wooliest parishes in Suffolk. There were plenty of people too, Blaxhall’s highest recorded population figure of 589 being achieved in 1861, though that number was reduced by one when 50 year old Mary Ann French fell foul of modern technology; she was working on the stage of a new fangled threshing machine when she lost her footing and got her leg caught between the drums. Several fellow workers (including her husband) managed to extract her from the contraption, but her leg was so badly mangled that she died from loss of blood. Ann was soon followed by 17 year old Robert Jay, who was also killed by a threshing machine a few months later. 1863 brought with it the discovery of a new batch of Roman artefacts when several urns were uncovered near Grove Farm, together with a number of coins dating from the reigns of Edward IV, William III and Anne, all less than a mile from the 1827 Tumulus. 1863 also saw more major work inside St Peter’s church, in the form of a restoration programme carried out under the direction of respected architect James Piers St Aubyn (1815-1895), (notably responsible for the Temple Church in London and major refurbishment of St Michael’s Mount in Cornwall). It was probably this restoration that was responsible for the disappearance of the Rood Screen - the existence of which (paintings and all) was noted in 1844 during a visit by the Reverend David Elisha Davy, a friend of Blaxhall’s rector Ellis Wade and prolific writer on Suffolk churches - though it may have gone earlier, during the work mentioned in 1857-58. This refit also brought an end to the gallery, where musicians playing flute, violin and cello used to accompany the hymns before the installation of the organ. Bits of the church weren’t the only thing disappearing at the time however, the 1871 census recorded a drop in the population to 546, though the number of available houses reached it’s peak at 122. That drop in population may well have been due to even more villagers leaving home in search of work, since London alone boasted over 60 Blaxhall born residents in the same 1871 census, (compared to only 30 in 1861). Some of them were apparently doing rather well for themselves too, owning coffee shops, pubs, and even a hotel - a far cry indeed from labouring on farms in Blaxhall, where average weekly wages were amongst the lowest for any job in the country, averaging as little as 7 shillings a week in 1851 and still only around 10 shillings weekly by 1870 (around £30 today). Whilst the live population was drifting away a couple of ex-residents made a reappearance on the occasion of the sexton unearthing two skeletons in the vicinty of the tower. Buried face down, it’s not known how they came to be there, but one possibility is that they were Pre-Christian (perhaps Roman) burials, while another speculation is that they were killed by falling debris from the ruinous tower (mentioned in the 1066 to 1699 article) and never recovered from the rubble. Most intriguing of all is the idea that they may have been accused of vampirism, since there was a belief long ago that such treatment would result in the "undead" digging down into the earth rather than rising up and chomping on the locals.

An unfortunate accident to one of those locals around this time proved to have something of a silver lining, when labourer James Sparrowhawk Smith - seen on the left outside the church c1870s - lost all but one finger in a chaff cutting machine; not to be downhearted however he turned his talents to mole catching and proved to be an absolute genius in that capacity. During one 32 day period in 1879 he caught no less than 654 moles, which was an extremely lucrative result since mole skin waistcoats were decidedly fashionable at the time! Blaxhall’s other businesses had also altered a little from its 1844 make up, there were now just 3 shoemakers and 1 blacksmith, but the village had gained a thatcher, a new shop, and a new wheelwright. The wheelwright, William Reeve, arrived with his family from Tunstall in the late 1860s, replacing his brother Robert who left to practice carpentry in Sussex. William’s son Walter, also a wheelwright/carpenter, can be seen with his son George in the photograph below, taken c1880.

The 1880s brought with them several changes and updates; the national school, which had been enlarged in 1879, was replaced by the Public Elementary School in 1881, while the old number 5 church bell, dating from 1655, was recast in London in 1881. Down at The Ship something of a new era was dawning when Samuel and Emma Meadows arrived to take over from Charles Abbott in 1880; Samuel and wife Emma (who both had one or two minor skeletons in their cupboards) only ran the Inn for around 3 years, but Samuel’s son in law John Hewitt was to fill the position for a full 43 years before his son Arthur took over for a further 38 years - between them spanning a period when The Ship would become famous for its music and singing, (and rather infamous for its fighting!)

100 years after Hodkinson gave us the first decent map of the village the Ordnance Survey produced their second view of the area. The layout they provided is very similar to the one we see today, with most of the current houses present and the road network virtually identical. Among the obvious discrepancies from today’s picture were the houses at Pump Square and Poplartree cottages, all of which vanished several decades ago. The apparent familiarity of this 100 year old scene is not unique however, as a couple of minor incidents recorded at the time remind us that some of today’s social problems are by no means a modern invention either; the first is an entry from the school log book which describes how two girls were severely punished for cruelly bullying a younger child with a "red hot poker" no less, while the second refers to the time that a large party of men marched from The Ship, in military fashion behind a trumpet player and mouth organ, in order to evict a party of travellers who had taken up residence on the common.

Another noteworthy event at this time was the loss of the windmill. Touted as one of the tallest postmills in Suffolk and the only one with four pairs of stones, Blaxhall mill burned down in January 1883, never to be rebuilt - though some some parts survived, finding their way to Brandeston, Peasenhall and Pettaugh. The miller, Edward Dykes, survived too -as did his wife and daughter, but apparently decided he’d had enough of milling and moved to Halesworth where he became a baker. The family’s bad luck didn’t stop there however - Edward’s brother James was killed when he was hit by the sail of his mill in Brandeston 5 years later. (It should be noted that the mill in question was located on Mill Common and also known as Dyke’s Mill, there was in fact a second windmill often called Blaxhall Mill which was actually in Little Glemham, located near the road junction behind the old water mill). No doubt encouraged by such misfortune people were becoming increasingly interested in safeguarding the future; already familier with a wide variety of savings organisations such as the Blanket Club, Coal Club, Clothing Club, etc, the village folk were encouraged by Pastor Wright to sign up for medical/life insurance. Things got a little fraught however when the good Pastor discovered that several members of the community had turned down his recommendation of the "Suffolk Provident Association" only to secretly sign up with the "Rational Sick and Burial Society" which was being proffered by Ship landlord John Hewitt.

As Blaxhall approached the culture shock of the 20th century the population was again on the rise, albeit for the last time. The residents in 1891 numbered 567, of which a remarkable 110 were attending school - a state of events that did not please the local farmers - many of whom saw the gaining of an education as being of secondary importance to the availability of cheap labour. Some people even blamed the poor condition of the roads (nothing new there then) on the fact that no children were available to collect stones for maintenance and repair. At the school's high point a couple of years later there were no less than 120 registered pupils, of which over 100 turned up on good days, but bad weather could reduce this by several dozen and illness took a major toll; serious outbreaks of diphtheria and the like would close the school completely for weeks at a time. There were numerous other things for villagers to attend, weather and health permitting, in the 1890s, including at least two church services every Sunday, Mothers' Meetings twice a month, Bible Class for men and Lads once a week in winter, and evening classes at the rectory in the study of insects & plants by microscope! Despite the aforementioned imminent arrival of 20th century technology and social change however some aspects of rural life remained stoically steadfast and true to tradition, as the lovely photograph below beautifully demonstrates; Shepherd George Smith is seen here with his flock in front of the church sometime in the 1890s, before moving to Aldeburgh to work for Captain Wentworth. The nephew of one fingered mole catcher Sparrowhawk Smith, George was evidently a popular man; following his death in 1905 a large party of people turned out to accompany his coffin all the way from Aldeburgh to Blaxhall, despite some decidedly grim weather.

Viewing a larger, high resolution copy of the photo clearly shows the original iron railings around two or three of the larger tombs in the graveyard that were later removed for the war effort. Also evident is the wooden fence and gate in the hedge opposite the south door, from which a path must have run alongside the hedge before joining the road. All this of course changed with the forthcoming expansion of the churchyard.

On a less religious note, the 23rd April 1892 saw those mischievous Lings manage one more misdemeanour before the century turned; this time it was a female indiscretion in the shape of Margaret Emma Ling stealing a glass from The Ship. Margaret’s husband Samuel, who was a great grandson of our old friend David, said he thought it was a very hard case, and having paid 30s of the £2 fine asked for extra time to pay the balance. The Magistrate gave him a week.

Staying on the subject of things official, Blaxhall Parish Council was formed in 1894.

Finally for this section; after several years of fundraising, saving and donations, the church organ chamber was completed in 1898 at a cost of £97, six shillings, and three pence. (£6100 today - seems pretty good value!)

Written by Shane Pictor 2003/04